Last week, the AFC Under-23 championship and Vietnam’s stunning run raised a few eyebrows on these shores, including some analysts and enthusiasts who thought that the win in China had come out of the blue.

Except that it hadn’t. Vietnam’s pedigree at the major championships at the youth level is at worst, a steady one and most definitely, a burgeoning one, based on years of consolidation through the ranks.

As the much touted and fancied Under-17 Indian men’s team failed to make it to the AFC Under-20 championships by winning one of their three qualifying matches, this meant that 2006 was the last time that India had qualified for the tournament.

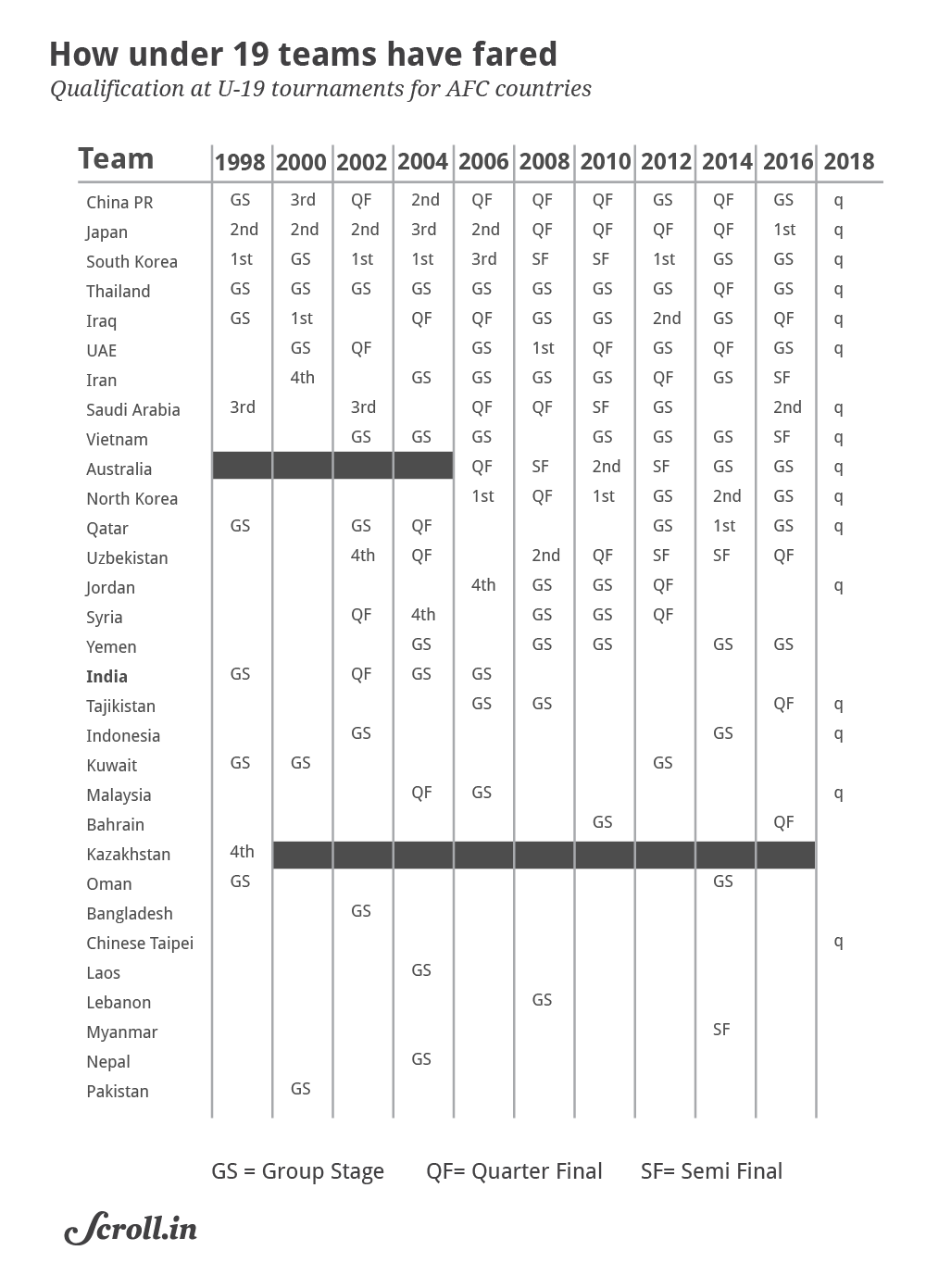

The failure of Amarjit Kiyam and Co meant that India had not made it to six straight continental finals. And as for Vietnam? 2008 was the last time that they had failed to make it to the AFC Under-20 finals. They had also qualified for the U-20 World Cup as a result of their performances in 2016, finishing as semifinalists in Asia.

Age group achievements over-valued

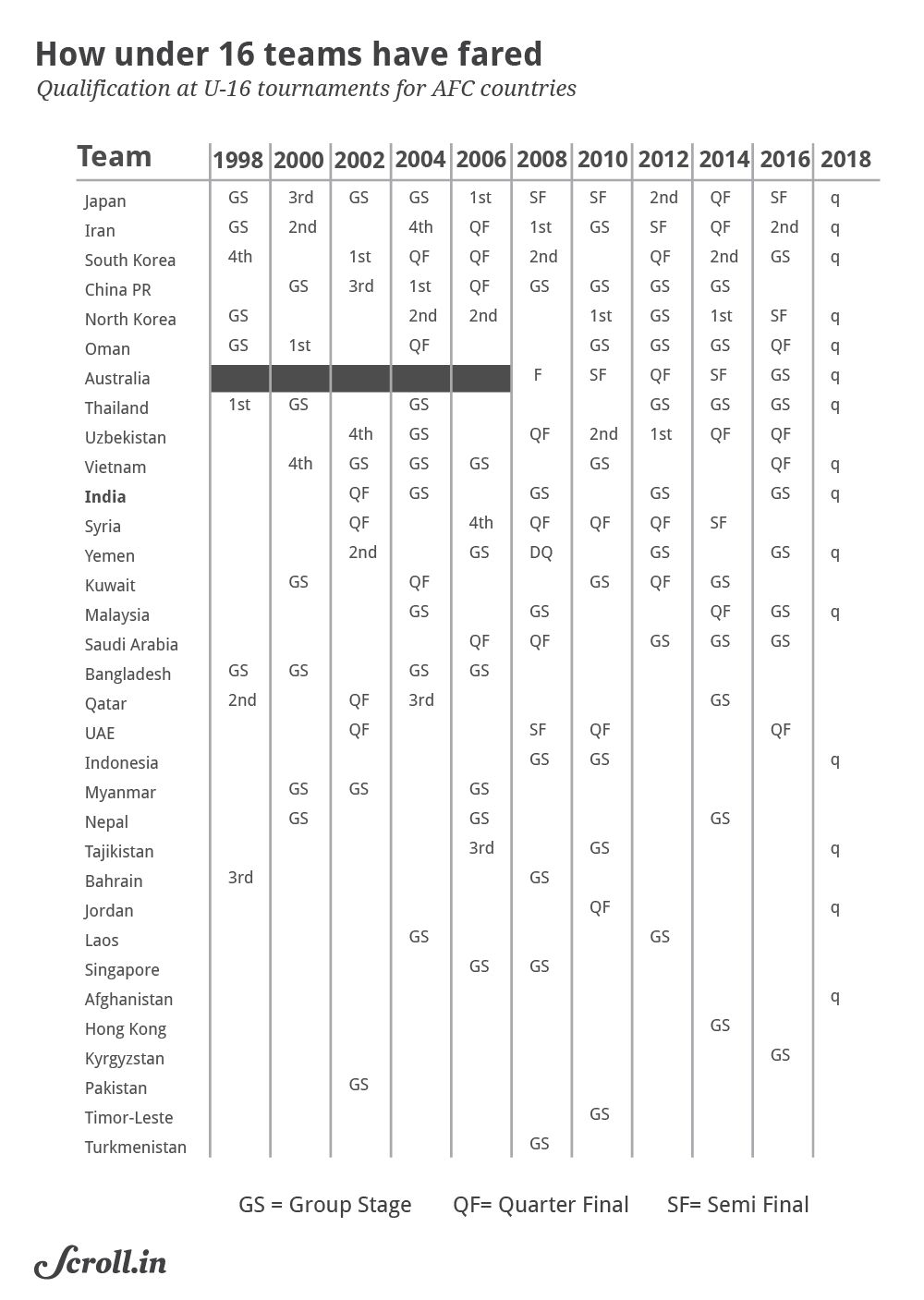

Indian authorities promptly patted themselves on the back after the Under-16 team made it to another AFC U-16 championships on merit, only the second time in history that they had reached consecutive tournaments.

But a look at the honour list of those, apart from the continental heavyweights, who have reached the tournament in recent years yield some interesting yet unfamiliar names: Afghanistan, Hong Kong, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Nepal, Tajikistan, Yemen.

Even tiny Timor-Leste qualified in 2010, so this really begs the question, how much of an achievement is it? The results at the the tournament have been far from satisfactory, with 2002 being the only time that the U-16 team made it beyond the group stage.

The U-19 story is an even more dire one, their last appearance coming in 2006 and India’s record of three tournaments reached since the turn of the century is matched or bettered by 19 nations, including Vietnam.

The Country that goes with the strategy of “Football Starts at Home”, will take one giant leap forward in development. You can spend millions of dollars at the top end of the game and it will not get you to where you really want to be. It’s that simple! pic.twitter.com/F4Cji73CiI

— Tom Byer汤姆.拜尔•トムバイヤー (@tomsan106) February 2, 2018

The same number of nations have qualified for the U-20 World Cup, Malaysia being the only nation to have solely done it by virtue of being hosts. India is not one of these countries. The AFC U-23 championships, where the top three teams qualify for the Olympics, has only been held three times and 21 teams have featured across editions.

Once again, India is not one of them, and failed to qualify for the 2018 edition, despite I-League and ISL first-teamers being part of the squad. The progression from U16 to U23 has only got tougher, despite many like Japan not taking the Under-23 competition seriously. This time around, the Blue Samurai had chosen to send their U20 team there, in order to prepare better for the Olympics.

Top to bottom approach

Steve Darby, one-time head coach of Mohun Bagan and also having managed the Vietnam women’s national team is considered somewhat of an expert in South-east Asia, having spent a considerable part of his managerial career in these parts.

“...the Vietnam Football Federation (VFF) have shown that there is benefit in long-term planning and they have invested Fifa and AFC (Asian Football Confederation) grants well in to building a top-class centre in My Dinh in Hanoi,” Darby says.

In their paths to develop the game, Vietnam and India are very much the anti-thesis of each other. While VFF has struggled with the V-League, its top-tier league, all the while building a solid youth platform, Indian authorities have pumped money into the top league and short-term fixes, while progress at the bottom is painfully slow.

While the All India Football Federation complains about a funds crunch, the money that does come its way is tossed around on the top layers and plans of hosting future tournaments and World Cups.

Neither the clubs nor the federation have shown an inclination of building from the ground up, with ‘catchment areas’ becoming more of a marketing term than priority action zones.

Baby Leagues a massive step

Possibly, the biggest development that had gone under the radar in 2017 is the introduction of the Baby Leagues. To start off with, these were started in two places, Chhampai in Mizoram and in Mumbai.

Predictably, the Mizoram Football Association (MFA) and the Western India Football Association (WIFA) are the most pro-active state associations in the country. Associations that may follow suit are Delhi and Meghalaya but a long-term Indian football insider insists on ‘not taking anything for granted until a couple of full cycles are executed.’

The concept of ‘Pony Leagues’ or Baby Leagues have paid handsome dividends in South America. Radamel Falcao, Luis Suarez, Carlos Tevez and many global superstars from the region, not necessarily named Messi, have come through the system.

The investment is a pittance when compared to the money that is spent on many youth festivals/tournaments/grassroots courses. The Young Legends League in Chhampai will occupy 756 footballers across 3 age groups for a period of 7 months, making it India’s longest-running league across levels.

GLIMPSE: The non-tangibles of the competitive experiences that a player's upbringing in the game needs from ages 5-21. A comprehensive calendar that will enhance competence in players, coaches and referees to global elite levels. Simple but not easy! pic.twitter.com/Hl5sH40UT5

— Baby Leagues India (@BabyLeagues_Ind) February 2, 2018

As tedious as it sounds, the Baby Leagues is the way to go but there mustn’t be a timeline attached to the project or a turnaround time. The odds that the project will yield dividends are very high, yet football development isn’t an easily-quantifiable subject.

With less than 0.1% of those playing youth football making it to the senior level, two Baby Leagues just isn’t going to cut it for a country of India’s size, nor is a ‘One Size Fits All’ model. For the footballing hotbeds of Bengal, Kerala, Manipur, Mizoram, Meghalaya and Punjab to be wholly tapped, the number of leagues would have to be in double digits, if not in three figures.

If Uruguay with a population of 3.5 million can have 60,000 children engaged in football, then the extent of work to be done for Indian football in this regard becomes crystal clear. For the ISL or I-League clubs to spend 4 lakh (5 or 6 in Tier-I cities) would require very minimal effort. Mumbai City have led the way, tying up with WIFA for a portion of the league. Bengaluru FC, have also started their own U-12 league.

Stop referring to the Under-17’s as ‘kids’

There are obvious short-term and long-term advantages of the Baby Leagues. Organised competition brings along with it prolonged exposure, both mentally and physically. At a younger age, it can also rope in parents into the game, who can give back to the effort on a voluntary basis. With more statistics and videos to pore through, scouting for the best players becomes a much easier effort.

The inculcation of a winning mentality at such a young age can be priceless and with advancing years, becomes a habit. So why is there a concerted effort to side-step the question of winning at a young age?

This writer has seen the U-17 team described as ‘our kids’, ‘boys’ or ‘children’ often on social media, in studios and in thinkpieces, praised for their ability to compete in a never-ending series of ‘learning experiences’. It is baffling to say that footballers, demanding first-team wages, wanting to be part of matchday squads and indeed, first XIs, must be treated with kid gloves and should be immune from criticism.

Pep Guardiola has made no exceptions for Player of the Tournament Phil Foden. In Germany, Jann Fiete-Arp starts and scores for Hamburg. Spain’s Sergio Gomez took a brave decision by moving to Borussia Dortmund, in search of more first-team action. USA’s Josh Sargent crossed the pond in order to sign for Werder Bremen.

It would be wrong to compare the Indian U-17 team with these footballers, but we can start by addressing them as footballers, as men who are out there on the pitch to win, not merely making up the numbers. It’s strange enough that a whole team must be built to accommodate the country’s best youth talents. The conclusion is as damning; barring one or two, they are nowhere near good enough to break into the first teams, hence the set-up of a different team to give them the requisite game time.

Exposure tours: why exactly do we need them again?

For the Under-17 World Cup, it was understandable that the AIFF wanted its own team to put up a decent show at home and sent the team on exposure tours, all over the world. While some of these matches were lopsided victories for the Blue Tigers, the exercise that paid off for the team were two matches against the Chandigarh Football Academy and the Minerva Academy, where the coaches bought in 9 players from the opposing teams.

Steven Martens, FIFA’s technical director, in an earlier interview with The Field had stated that ‘exposure tours are unsustainable in the long term.’ While the prescribed formula world over is to play 70 games, 60 of them at home, the next batch of the Under-17’s have also been sent on similar exposure tours.

The same tonic, was prescribed, rather hilariously for the senior men’s team ahead of the 2011 Asian Cup. One fails to see how a bunch of footballers in their prime could be exposed to anything that would drastically change their playing styles.

By 16 or 17, the process of skill exposure is almost finito, especially if up against weak opposition with the sole option of injecting some confidence into your own team. The old adage, ‘practise makes perfect’ holds true but for a footballer, this process must start at 6-7, accumulating in tens of thousands of playing hours by 17-18.

Setting up Elite Academies for 16-19 year-olds, sending them to exposure tours, give an impression of branding the cow once it has escaped the shed. For a federation, which claims to be cash-strapped, it simply seems to be a case of throwing worse money after bad.

Painting the top floor and setting up a casino in a crumbling building may attract fair-weather visitors but for repeated visits, the base needs to be shored up and cemented in place. Without a base, all Indian football has is paint smirched all over.

As much as we’d like to believe, there are no short-term fixes for Indian football. Administrators may not want to put in place policies which affect the sport beyond their tenure, but that does not change the fact that Indian football is unlikely to turn around during any single administrator’s reign. If Japan can have a 100-year plan, the least we can do is take a look at it and ponder why. Rather why not.